The Intention to Endure: Memory, Change, and the Stones of Beijing

Personal reflections on preserving knowledge in a world shaped by impermanence.

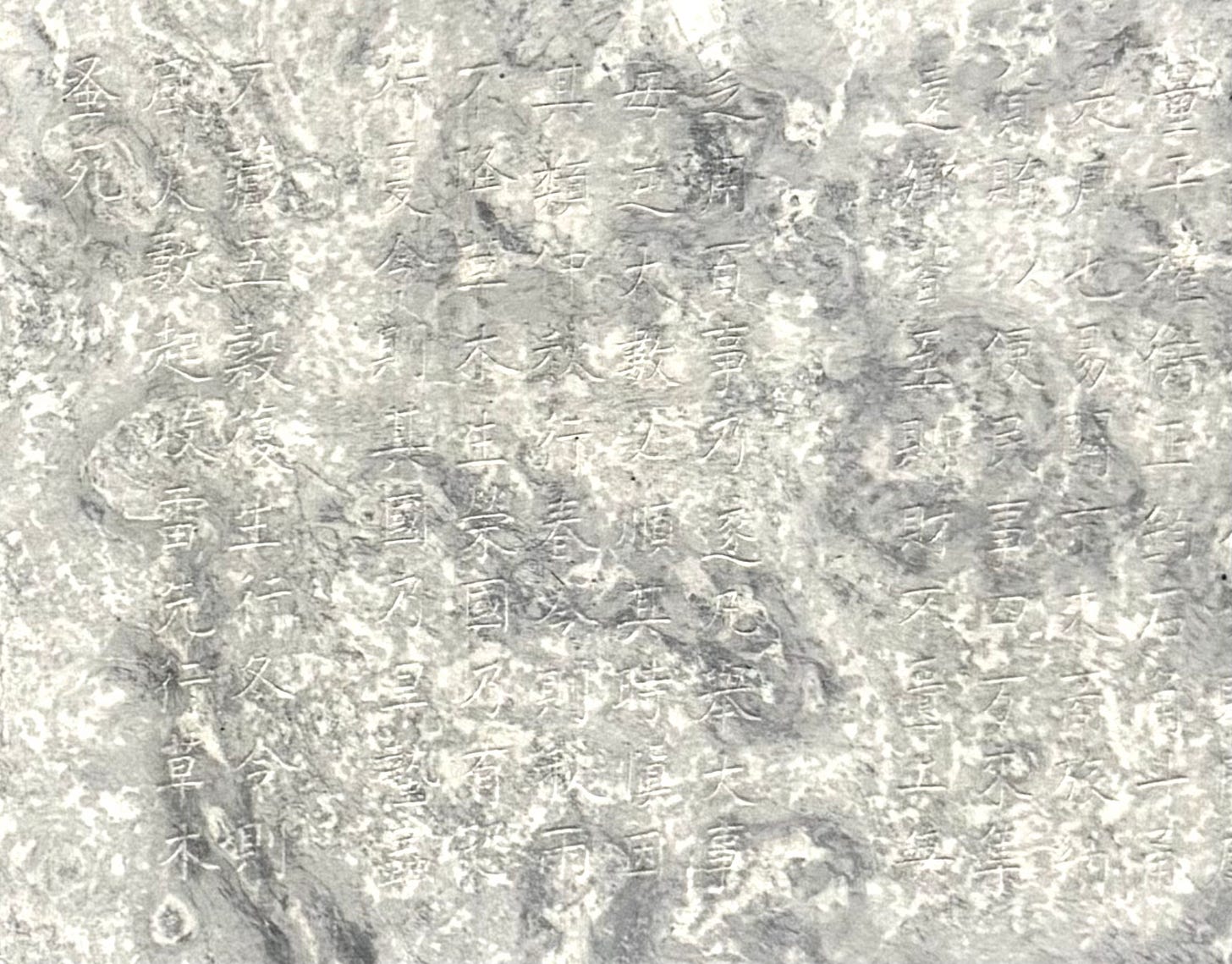

Last week, I stood before the Qianlong Stone Steles at the Confucius Temple in Beijing.

Towering slabs of stone, densely engraved with classical texts, they form a monumental archive — a deliberate act of preservation undertaken more than two centuries ago.

At first, it was their physical scale that struck me.

But standing there longer, I was drawn to something deeper: the recognition that these were not monuments to conquest or empire.

They were monuments to memory — to the belief that certain knowledge is too important to entrust to the accidents of history.

As someone who has spent much of my professional life advancing the role of data in accelerating scientific discovery, the experience felt particularly resonant.

It forced a question that has stayed with me:

What are our Qianlong Stones? What knowledge will endure from our time?

History makes clear how easily knowledge can disappear.

The Library of Alexandria, where centuries of thought were reduced to ash.

The Qin Dynasty’s destruction of rival philosophical works.

The fall of Constantinople and the loss of classical manuscripts.

The sack of Baghdad’s House of Wisdom, where rivers ran black with the ink of drowned books.

The disruption of Indigenous oral traditions, where languages, ecological knowledge, and histories were severed, often irreversibly.

In each case, the losses were profound.

Entire systems of understanding — entire ways of imagining the world — were erased.

The Qianlong Stone Steles were commissioned against this backdrop of human fragility.

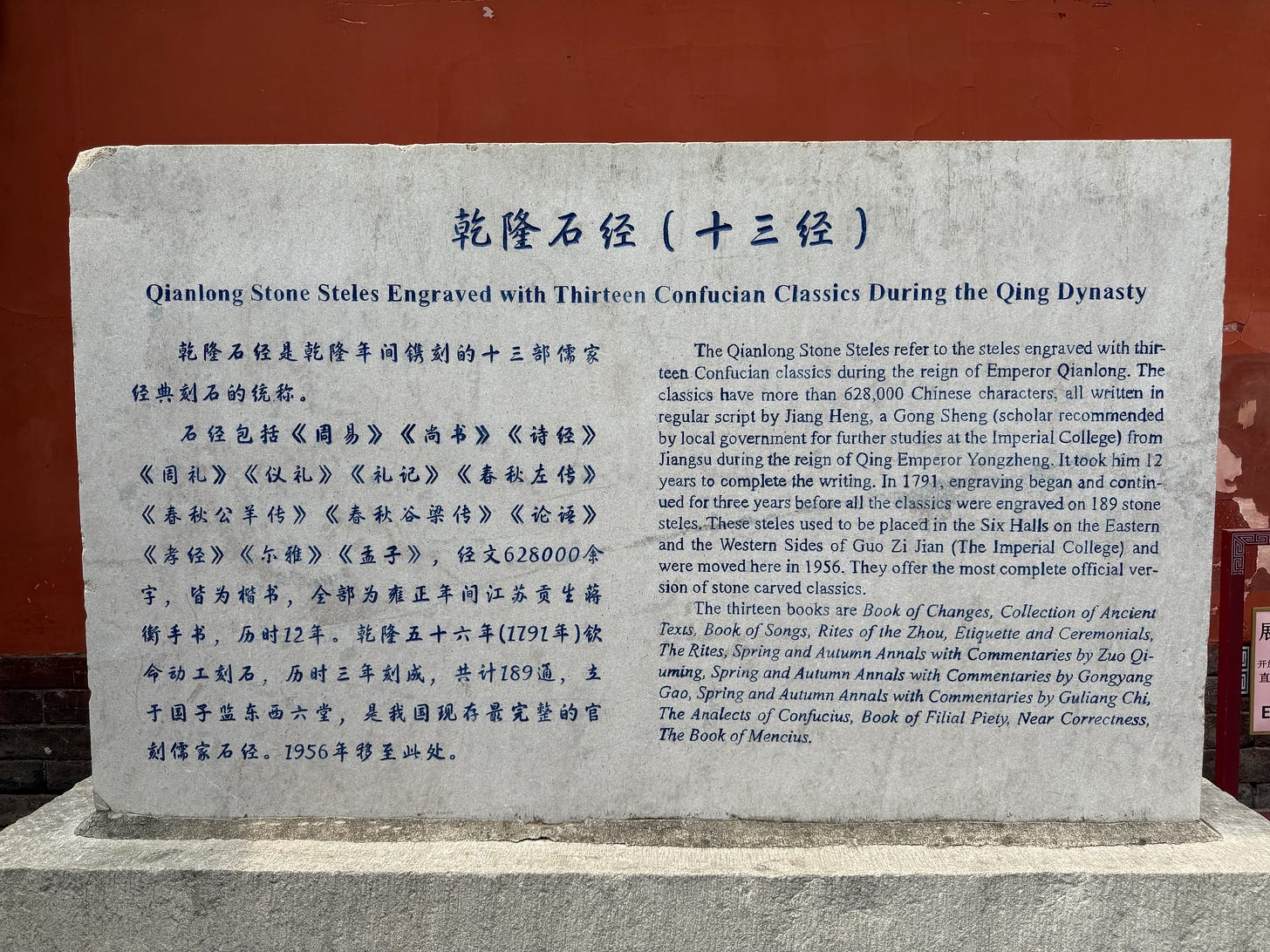

In the eighteenth century, the Qianlong Emperor ordered the full engraving of the Thirteen Confucian Classics onto stone.

This was not a decorative project. It was a survival strategy — a conscious choice to protect essential knowledge against political upheaval, material decay, and historical forgetting.

The texts engraved included:

The Book of Changes (易经, Yìjīng) — a foundational text of cosmology and divination, reflecting ideas about change and natural order.

The Book of Documents (书经, Shūjīng) — historical speeches and records on early governance.

The Book of Songs (诗经, Shījīng) — the earliest anthology of Chinese poetry, documenting social life, rituals, and emotion.

The Book of Rites (礼记, Lǐjì) — a manual of ceremonies and social norms critical to maintaining social order.

The Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋, Chūnqiū) — a terse historical chronicle attributed to Confucius.

The Zuo Commentary (左传, Zuǒzhuàn) — a narrative expansion offering political and ethical insights.

The Commentary of Gongyang (公羊传, Gōngyáng Zhuàn) — a moral interpretation of the Annals.

The Commentary of Guliang (谷梁传, Gǔliáng Zhuàn) — an alternative commentary tradition.

The Analects (论语, Lúnyǔ) — the sayings and conversations of Confucius and his disciples.

The Classic of Filial Piety (孝经, Xiàojīng) — a reflection on the central role of filial duty.

The Erya (尔雅, Ěryǎ) — an early dictionary and encyclopedic text clarifying classical vocabulary.

The Mengzi (孟子, Mèngzǐ) — the teachings of Mencius on human nature and benevolent governance.

The Lesser Learning (小学, Xiǎoxué) — a manual for early education in proper conduct and language.

Together, these works formed a complete intellectual system: philosophy, ethics, governance, ritual, history, and language.

Preserving them fully — not as fragments, not as selected quotes — was an act of cultural continuity, a commitment to safeguarding meaning itself.

Among these texts was the I Ching or The Book of Changes — a work devoted to the ceaseless transformation of nature and human affairs.

Preserving a philosophy centered on change by carving it into stone was not ironic; it was a recognition that because change is inevitable, certain insights must be intentionally safeguarded.

Today, we face a similar challenge: the very forces that allow us to create and distribute knowledge at unprecedented speed — technological change, fluidity, evolution — also threaten the long-term preservation of what we know.

Without deliberate effort, even our understanding of change itself risks being lost to the transformations we fail to anticipate.

Not everything must be preserved.

Change is natural, and forgetting can be as necessary as remembering.

But deliberate preservation is an act of judgment — a recognition that some knowledge, some frameworks, some hard-won insights are too essential to abandon to the tides of impermanence.

The challenge is not to save everything, but to care enough to save what matters most.

Today, the volume of information we produce dwarfs anything imaginable in the eighteenth century.

Yet the physical and digital foundations of our knowledge are precarious.

Magnetic media degrade.

Hard drives fail.

Digital formats evolve and become unreadable within decades.

Archives vanish not through fires or invasions, but silently — through technological obsolescence, institutional neglect, or shifting legal and economic pressures.

Even in an era of cloud storage and global replication, knowledge remains far more fragile than we often assume.

The recent legal and financial challenges faced by the Internet Archive — one of the world’s most important efforts to preserve digital books, records, and web history — serve as a sharp reminder.

Despite its mission to safeguard access to human knowledge, the Archive has been forced by litigation to remove significant portions of its collections, showing how even preservation efforts rooted in public service can be dismantled.

At the same time, cybersecurity breaches and sustained attacks have revealed just how vulnerable even our most robust digital institutions can be to disruption.

We have built knowledge empires on foundations that cannot last.

If institutions like the Internet Archive — built explicitly to protect memory — can be so easily threatened, it is a stark warning for the broader fragility of our digital infrastructure.

Standing before the Qianlong Stones, I was reminded that preservation is never incidental.

It requires foresight, material choices designed for endurance, and a recognition that knowledge belongs not only to the present but to the future.

Today, we are challenged even to ensure that our most essential scientific data and knowledge are robustly preserved.

The foundation of the modern world — our health, our technologies, our understanding of the natural world — depends on it.

Yet we continue to build knowledge systems that prize speed and convenience over durability.

We risk losing not only isolated works, but entire architectures of meaning and discovery — just as previous civilizations did, often without realizing it until too late.

If we do not act with care and foresight, it will not be fire or conquest that erases our memory.

It will be silence.

The silence of corrupted drives, obsolete formats, abandoned archives — and a future that asks questions to which no answers remain.

The Qianlong Stones endure because someone believed that certain knowledge was worth carving into permanence.

We must decide, clearly and deliberately, whether we believe the same.

Sean Hill — 26 April, 2025